Medicine in Vienna has been relied on for centuries

Even when the trigger is a sneaky virus like COVID-19 – locals and guests alike can rely on the city's health infrastructure. The reasons for the strengths of medicine in Vienna extend way back in time. The Medical Faculty of the University of Vienna was an entity as early as the Middle Ages. It attained international importance after Gerard van Swieten, who was called to Vienna by Archduchess Maria Theresa in 1745, laid the foundation stone of the first Vienna Medical School. Renowned individuals worked here. With the opening of the General Hospital (AKH) in 1784, the physicians acquired a place of work that was to develop into the most important research center and give rise to the second Vienna Medical School in the course of the 19th century.

Anatomical studies

The basis for success was laid by anatomical studies that were advanced by the pathologist Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky (1804-1878) and the internist Joseph Skoda (1805-1881). An institution dating back to the time of Joseph II played an important role as a training center for future physicians: the Josephinum, founded in 1785 as a surgical-military academy. The building is currently undergoing general restoration. It should be possible to view the world-famous anatomical wax models again in 2021.

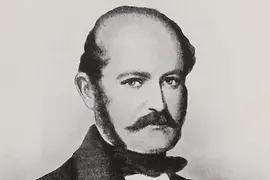

In obstetrics, too, the new science-based research had an impact. Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (1818-1865), dubbed the "father of hand washing" by the medical historian Herwig Czech, is returning to prominence due to coronavirus. He developed a new theory of childbed fever, which unleashed much controversy among the medical profession. Although the avant-garde of Viennese medicine supported Semmelweis, his career in Vienna ran aground on the opposition of conservative professors.

Many other disciplines received important stimuli from the middle of the 19th century. Psychiatry, most closely associated with the name Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), is just one of them. Particularly spectacular were the advances made in surgery. Franz Schuh (1804-1865) performed the world's first successful pericardial puncture in 1840. The highest achievements of Viennese surgery were embodied by Theodor Billroth (1829-1894), who introduced consistent asepsis through "cleanliness to the point of debauchery".

In the discipline of Internal Medicine, the University of Vienna had a leading representative in Hermann Nothnagel (1841-1905). His student Guido Holzknecht (1872-1931) worked on the applicability of X-rays in diagnosis and therapy. The Central X-Ray Institute set up and run by him at the AKH became a training center for radiologists from around the world.

Nobel Prize winners

The international importance of Viennese medicine was also reflected in Nobel Prizes. In 1914, Robert Bárány (1876-1936) received the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his experimental research into the function of the vestibular apparatus. In 1927, the neurologist and psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857-1940) was putting his methodically scientific roots down in the field of experimental pathology. Around 1917, he researched the method for healing the progressive paralysis caused by fever.

The "core subject" of the second Vienna Medical School, pathological anatomy, also originally produced the Nobel Prize winner Karl Landsteiner (1868-1943), who discovered the blood groups while working as an assistant to Anton Weichselbaum (1845-1920) in around 1900. In 1930, he was honored for this with the Nobel Prize for Medicine. In 1936, Otto Loewi (1873-1963) received this prize for the experimental proof of the chemical transmission of nerve impulses. In 1938, he was forced to hand over his prize money to the German Reich in return for being allowed to emigrate.

Although Viennese medicine still had a high reputation after the Second World War, the "Anschluss" of 1938 marked the end of a scientific heyday that was to a large extent due to Jewish doctors.

Medical University of Vienna in the top league

However, time has not stood still. Today, the Medical University of Vienna has around 8,000 students and ranks among the largest medical training facilities in the German-speaking region. With its 29 university clinics and clinical institutes, twelve centers for medical theory, and numerous highly specialized laboratories, it is one of Europe's most important top-level research institutes in the field of biomedicine.

Across Vienna there are 45 health facilities, of which 17 hospitals and care homes are run by the city. With 685 doctors per 100,000 inhabitants, Vienna ranks third in the EU. The AKH also exerts a huge influence beyond the limits of the city and country; it is, for example, one of the world's four leading centers for lung transplants.